What is the eye and how does the eye work?

Share

What is the human eye?

The human eye is an approximately spherical bag of living cells 2.5cm across, filled with transparent jelly and a pressurized liquid that keeps it inflated like a balloon.

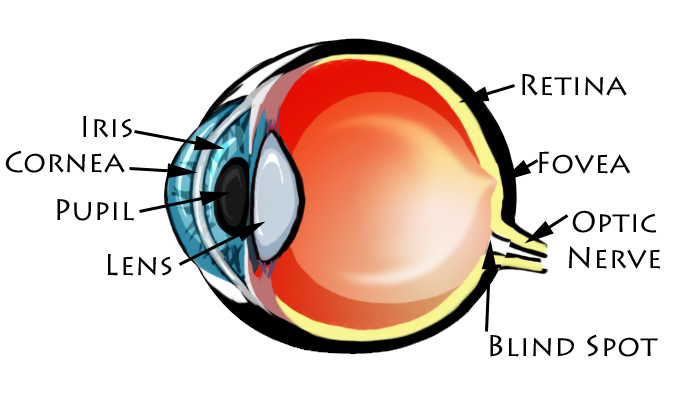

At the front of the eye is the cornea, which is a window of transparent cells that allows light to enter.

Just behind the cornea is the iris, which is an opaque diaphragm of coloured muscle that regulates the amount of light entering the eye.

The pupil is the dark hole in the centre of the iris, which becomes larger or smaller as the iris expands or contracts. Immediately behind the iris is the inner lens, which is a transparent capsule of cells with the consistency of rubber that focuses light onto the retina at the back of the eye.

Although the eye is usually compared to a film camera, a television camera is a better analogy because the retina is composed of specialized cells that convert light into the electrical impulses that travel up the optic nerve to the brain.

Every 40th of a second, the retina can transmit a new image consisting of more than 100 million bits of information.

Until recently, it was thought that visual perception took place only in the brain, but it is now known that the retina, which is a complex and

highly organized network of nerve cells, processes the raw image for basic information such as outlines, colours, and motion.

The brain then completes the processing and derives more information about detail, distance, and dimension, which adds meaning and integrates the data into what you actually see.

It's also worth noting that the retina seems to possess a rudimentary form of intelligence and many scientists now regard it as an extension of the brain.

How does the human eye change focus?

The eye's optical system consists of two major components: the cornea and the inner lens. The cornea has almost three times as much refractive power as the inner lens.

Light first passes through the cornea, which partially focuses it, then passes through the inner lens, which completes the focusing onto the retina and can adjust the focus as needed.

The eye changes focus action between objects at different distances by the of the ciliary muscle on the inner lens, thereby adjusting its shape and refractive power.

It has also been theorized that muscles can respond to the extraocular emotional stress by changing the length of the eyeball and may play a minor role in the focusing process.

The ciliary muscle, a circular muscle similar to the iris, is attached to

the inner lens through a microscopic meshwork of fibrous filaments known as the zonule of Zinn. When the ciliary muscle expands, it makes the inner lens thinner and reduces its refractive power so that far objects are focused onto the retina.

When the ciliary muscle contracts, it makes the inner lens thicker and increases its refractive power so that near objects are focused onto the retina.

How does the human eye move around?

Six extraocular muscles surround each eyeball and move the eyes so that they point at the same object at the same time.

The power and precision required is truly amazing. During the course of a rapid eye movement lasting about a tenth of a second, the eyeball accelerates at a tremendous rate and decelerates almost instantly.

To generate enough power to do this, the extraocular muscles are approximately 200 times stronger than would be needed to slowly turn the eyes in their sockets.

The eyes are constantly looking from object to object, detail to detail, as they scan the world and gather information. For example, to read these words, your eyes are automatically jumping from one group of letters to the next.

These jumping movements are known as saccades. When the eyes follow a moving object, they make a different type of movement known as pursuits, which are smooth and continuous. Finally, there's another type of movement known as slow drifting. If you stare at a small dot for more than a few seconds, your gaze

will periodically drift away, then return to the dot. In normal healthy eyes, the ciliary and extraocular muscles work together as a team, constantly adjusting to the world around us.

The brain is in complete control and makes the eyes point and focus on the same object at the same time as they constantly search for new objects of interest.

If the ciliary muscle malfunctions, the eyes go out of focus. If the extraocular muscles malfunction, the eyes may point at different objects. This is usually experienced as double vision, headaches, eye- strain, suppressed vision, slow reading, poor depth perception, tendency to bump into things.